Science of Reading Reforms in Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Tennessee

A review of the literature

by John Morrison

August 22, 2025

Examples of People Doubling Down on Old Literacy Programs

APM Reports revealed in April 2024 that the Ohio State University and Lesley University continued to defend their literacy training programs that promote cueing. Teachers College at Columbia did likewise until 2023, when it announced it would shift to research-backed methods.

The three development programs at Lesley University, Ohio State, and Teachers College have worked with hundreds of thousands of educators in school systems all over America, including New York City, Houston, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Columbus, Ohio, and around thirteen districts in New England.

APM Reports notes that some phonics is included, but that the programs at Lesley and Ohio State instruct students on how to use context clues to decipher words.

The article notes that cueing was popularized by Gay Su Pinnell, who founded Ohio State’s Literacy Collaborative, and Irene Fountas, who founded and continues to direct Lesley University’s Center for Reading Recovery & Literacy Collaborative.

Stephanie Spadorcia, Lesley’s vice-provost of education, described Fountas as “a pioneer” and said Lesley University is “very proud of our history and affiliation with Reading Recovery.” But she noted in an interview with APM Reports:

“My colleagues at the Reading Recovery Literacy Collaborative would be the first ones to say we know that our approach does not work for every kid. It’s an option; it’s a choice. We see it still being a very important option to have in school districts.”

A spokesperson for Ohio State University told APM Reports that it had no plans to change its training.

Between 2013 and 2023, Ohio State’s Literacy Collaborative brought in an average of $3 million every year.

The programs have been so lucrative that Gay Su Pinnell was able to donate $9.5 million to Ohio State and $3 million to Lesley.

In 2024, the California Teachers Association opposed new legislation that would’ve mandated the science of reading and did not suggest any amendments. A compromise meant funding was approved for the science of reading, but the mandate was dropped.

The California Teachers Association (CTA) is the state’s biggest teachers union and originally supported Senate Bill 488 in 2022, which, according to EdSource, “requires a literacy performance assessment for teachers and oversight of literacy instruction in teacher preparation.”

But the union reversed its position when it then opposed Assembly Bill 2222, which would’ve mandated the science of reading.

The CTA outlined its complaints in a long letter; some of these issues included: undermining current literacy initiatives, not meeting the needs of English learners, and removing teachers from the decision-making process.

Commentators attribute the reversal to a survey of 1,300 CTA members who said the assessment from the 2022 Bill caused stress and ate up their time.

Marshall Tuck, CEO of EdVoice, says the CTA misunderstands the bill and the science of reading:

It “is not a curriculum and is not a program or a one-size-fits-all approach,” he said.

“It will give teachers a foundational understanding of how children learn to read. Teachers will still have a lot of room locally to decide which instructional moves to make on any given day for any given child... So, you’ll still have significant differentiation.”

Claude Goldenberg, professor emeritus of education at Stanford University, said the CTA did not suggest any amendments and met with their representatives to ask them to identify changes.

In 2025, the opposing sides reached a compromise that approved funding for phonics instruction but removed the mandate to teach it.

In March 2023, the presidents of the Ohio Federation of Teachers and the Ohio Education Association opposed Governor Mike DeWine’s push to ban “cueing” and other instructional practices, even though they support the science of reading as a concept.

Scott DiMauro, president of the Ohio Education Association (OEA), said that there’s no need for bans if the state provides the training and resources needed to implement the science of reading:

“I would strongly, strongly urge the house to consider removal of language that explicitly bans any particular instructional practices.”

“There’s no need for the heavy hand of the state government to single out any specific instructional practices.”

Melissa Cropper, president of the Ohio Federation of Teachers (OFT), said it’s wrong to ban methods when there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to literacy instruction:

“Banning certain methods opens the door to politically-charged attacks that can limit a teacher’s ability to choose the most appropriate method for meeting a student’s needs.”

“There has been no analysis done on which districts are using which teaching methods or curriculum… Many other factors contribute to students’ academic success including their socioeconomic status.”

Researchers at University College London (UCL) published a 2022 study that criticized phonics as “uninformed and failing children” in England. Unfortunately for the researchers, international rankings published just afterwards found that English schoolchildren were among the best readers in the world.

The Guardian reported:

“Researchers at UCL’s Institute of Education say the current emphasis on synthetic phonics, which teaches children to read by helping them to identify and pronounce sounds which they blend together to make words, is “not underpinned by the latest evidence”.”

“They claim analysis of multiple systematic reviews, experimental trials and data from international assessment tests such as Pisa suggests that teaching reading in England may have been less successful since the adoption of the synthetic phonics approach rather than more.”:

The UCL researchers were among 250 signatories to a letter sent to the then Education Secretary to allow more approaches to literacy instruction and to give teachers the power to decide what’s best for their students.

But even the Guardian reported on England’s success in international rankings and cited the schools minister who said improvement in reading followed the 2012 switch to phonics.

As someone living in the UK, I can confirm that no one takes these kinds of academics seriously, and the only attention they get is the occasional press release picked up by the Guardian.

While Lucy Calkins has revised her curriculum, critics note that she still benefits financially from this pivot. And in a notable 2022 New York Times profile, she refused to apologise for anything and asked for an apology from proponents of phonics.

Dana Goldstein writes in a May 2022 profile that Calkins updated her reading curriculum to, for the first time, include daily structured phonics for the whole class. This curriculum for kindergarten to second-graders went on sale in summer 2022.

While Calkins has appeared to show some humility over the debate, Goldstein also noted the following:

“Professor Calkins does not believe she has anything to apologize for. She pointed out that some partner schools, like P.S. 249, a high-poverty, high-performing school in Brooklyn, have embraced a separate phonics supplement she published in 2018.”

“And, she asked, shouldn’t the phonics-first camp apologize? “Are people asking whether they’re going to apologize for overlooking writing?” she said.”

Even when Calkins updated her curriculum, she made the following statement in a separate instance:

“To reduce the teaching of reading to phonics instruction and nothing more is to misunderstand what reading is, and what learning is.”

Indiana has used “three-cueing” and balanced literacy instruction methods for years despite poor results. But the state teachers’ union secretary and some teachers have opposed the state’s move to phonics, which includes 80 hours of training.

Dianna Reed, secretary of ISTA, said the training has “compounded existing challenges of teacher burnout and retention.”

“Colleagues have expressed they would rather let their licenses lapse at the next renewal date, than be subjected to more hoops and mandates to prove their worth.”

Many teachers criticized the eighty hours of training as “excessive” and “burdensome.”

The 2018 NAEP Oral Reading Fluency Study

Students reading at an NAEP Advanced level read around 160 words correctly in one minute, NAEP Proficient students read around 142 words, NAEP Basic students read 120 words correctly in one minute, while those below NAEP Basic read on average 91 correct words per minute.

Around a quarter of white students score in the NAEP Basic group, compared to just under half of Hispanic students and just over half of black students. There’s a 3:1 ratio of white students to black and Hispanic students in the NAEP advanced groups. Eligibility for school lunches is another predictor.

In absolute numbers, an estimated 1.27 million fourth-graders fall in the NAEP Basic group, including a roughly equal number of black and white students, despite white students being a larger group.

The study then broke down students in the below NAEP basic category into three subcategories: below NAEP Basic Low (the bottom third of this bottom group), below NAEP Basic Medium (the middle third), and below NAEP Basic High (the top third). Black and Hispanic students again performed the worst.

NAEP Basic Low fourth-graders have the following characteristics (Page 44):

“Read connected text with difficulty—at half the WCPM of a fourth-grader performing at the NAEP Proficient level”.

“Misread 1 out of every 6 words”.

“Focus on individual words, phrases, or clauses instead of the meanings of sentences and passages”.

“Read in a voice that is arrhythmic or monotone, indicating lack of text comprehension”.

“Recognize with difficulty whole words they are likely to know when listening or speaking”.

“Show limited knowledge of spelling-sound correspondences”.

In absolute numbers, some 420,000 fourth-graders score in the very lowest subcategory of the NAEP below basic group. This includes one out of five black students in fourth grade and one out of six Hispanic students.

The study found a pattern of decreasing performance on every measure of oral reading fluency, phonological decoding, and word reading, from the highest to the lowest-achieving groups. The most important gap was found in passage reading accuracy; more details on that below.

For words correct per minute (WCPM), the gap between NAEP Advanced and the lowest subcategory of NAEP Basic Low was 89 points.

For the average passage reading rate, the gap between NAEP Advanced and the lowest subcategory of NAEP Basic Low was 77 points.

For passage reading accuracy, the gap between NAEP Advanced and the lowest subcategory of NAEP Basic Low was 16 percentage points.

The study flags this as perhaps the most important difference. A student reading at 90% accuracy is missing one out of ten words compared to one out of twenty words for a student reading at 95% accuracy.

A reading passage accuracy of 82% means a student misreads one out of every six words.

Such a frequent misreading of words means a student will have difficulty understanding texts because these misunderstood words tend to be important content words.

Because an average sentence is 14 words, even the NAEP Basic-Medium score of 92% means a student misunderstands a word in practically every sentence (Page 36 of study).

For passage reading expression, the gap between NAEP Advanced and the lowest subcategory of NAEP Basic Low was 2 levels.

A fourth-grader reading at Level 4 can “correctly express text and sentence structure and meaning” of continuous text.”

A fourth-grader reading at Level 3 can “correctly express the meaning of phrases and clauses but not the passage as a whole.”

A fourth-grader reading at Level 2 focuses on individual words, but not sentences, phrases, or passages as a whole.

For average word reading WCPM, the gap between NAEP Advanced and the lowest subcategory of NAEP Basic Low was 25 points.

For average pseudoword reading WCPM, the gap between NAEP Advanced and the lowest subcategory of NAEP Basic Low was 20 points.

Breakdown of scores by NAEP reading achievement level

Breakdown of scores by the NAEP Below Basic subgroups below

A Combination of Interventions and Factors That Seem to Produce Results

The 74 has a useful interactive tool that allows you to see which school districts are performing above expectations according to the poverty rate. Meanwhile, the Education Recovery Scorecard accounts provide one national standard for schools in their post-pandemic recovery phase, while accounting for differing state tests.

Substack article that created similar graphs using free school meals as the metric

Districts that credit phonics to some extent

Atlanta Public Schools.

Steubenville City School District.

Palo Alto Unified School District Board.

Miami-Dade.

Steubenville subsidizes pre-K, where it encourages students to talk in full sentences, which prepares them for learning to read and write. It also has programs to help with attendance, tutoring, and practice time. Steubenville uses all teachers to teach smaller reading classes that are grouped according to ability, which thus mixes students across grade levels - perhaps an alternative to retention.

Steubenville City Schools is one of the poorest districts in Ohio, but for over 15 years, it has achieved some of the best third-grade reading scores in the country. Some of the strategies it implements include:

Subsidized pre-K - Less than half of children in America attend a preschool program, but in Steubenville, that number is almost eighty percent. What’s more, pre-K teachers in Steubenville encourage students to talk in full sentences, which helps them when they eventually learn to read and write.

Attendance - In Steubenville, a class of thirty children typically has around two chronically absent students compared to six or seven in Ohio generally. The schools use attendance contents to motivate students and a rapid response team when they’re absent.

Small reading classes - Steubenville’s schools teach all reading classes at the same time, so students can be grouped by ability, even if that means mixing with different grades. Classes remain small because every teacher leads one, including gym teachers.

Practice time - Steubenville’s schools allocated time for “cooperative learning” so kids can work in pairs and small groups according to their skill level.

Tutoring - Students get a daily ninety-minute reading class, but struggling students get additional one-on-one tutoring. This can be from staff, local volunteers, and local high school and college students.

Consistency - Steubenville has stuck it out with the Success for All program for twenty-five years.

A Substack I came across points out that Steubenville uses a heavily phonics-based curriculum, which other schools are reluctant to use because of its restrictions. The post also notes that Steubenville’s gains don’t carry through to later years.

“Steubenville picked a reading curriculum that is heavily phonics-based and has had a top-to-bottom commitment over many years to implementing that curriculum faithfully, including constant monitoring of students’ progress.”

“Other districts are loathe to copy Steubenville’s example because the curriculum is very prescriptive. It specifies exactly what teachers are supposed to do every day. This arouses opposition in other districts because it is thought to impinge on individual teachers’ autonomy to plan their lessons as they see fit.”

“Even at Steubenville, this hard-won outperformance does not carry through to middle and high school grades.”

Steubenville is an obvious outlier in Ohio - from a Substack article that created similar graphs using free school meals as the metric

A 2018 study analysing sixty previous studies found that coaching improved learning by four to six months. The tutoring factor played out during the pandemic when many districts used relief funding to pay for extra tutors, with some making headlines for bucking trends in declining standards.

According to Chalkbeat, the 2018 Brown study summarized “the results of 60 prior studies found that coaching accelerated student learning by the equivalent of four to six months.”

The District of Columbia Public Schools system scored first among states for maths and reading gains between 2022 and 2024. The district used pandemic relief funding to hire extra tutors.

The school district ranked first in the Education Recovery Scorecard for maths and reading gains between 2022 and 2024.

The district used pandemic-relief money to fund extra tutors, which it said also helped improve attendance. The scorecard found a link between absenteeism and learning difficulties.

Compton district hired hundreds of maths and reading tutors to provide extra tutoring around the regular timetable, but also to staff specific classes with extra tutors to help teachers.

The Compton school district hired more than 250 maths and reading tutors.

Multiple tutors were assigned to specific classes to help teachers.

Schools in the district provide tutoring for before, during, and after school, as well as Saturday School and summer programs.

The Compton district also carries out dyslexia screenings in all its elementary schools to identify kids who will need targeted help.

The Palo Alto Unified School District Board saw double-digit growth in nearly all groups, especially low-income Hispanic students, in just a year. The district board credited teacher training, on-the-job support, curriculum interventions like ditching Units of Study, reading assessments, and various leadership moves. More details below.

Todd Collins, a member of the Palo Alto Unified School District Board, wrote in Ed Source of the improvements, wrote an article in EdSource about his district’s quick gains and the measures they used.

Teacher training:

“The district uses the Orton-Gillingham (O-G) training, a leading method for teaching reading foundational skills, for all K-three teachers, reading specialists, and all elementary principals.”

“Reading-focused optional after-school workshops are available for TK-five teachers and elementary specialists.”

“Teachers receive curriculum and assessment-specific training.”

Coaching and on-the-job support:

“The district provides ongoing support to teachers with implementation of the new curriculum.”

“There is now a repository of high-quality resources for teachers on reading instruction including instructional materials and videos.”

“The team leading the initiative has weekly communication with elementary educators.”

Reading curriculum and interventions:

“The Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study, criticized for lack of foundational skills, has been replaced by the widely used Benchmark Advance/Adelante plus O-G foundational skills and “decodable” texts.”

“Schools offer targeted interventions for students who need additional support focused on phonemic awareness and phonics.”

Reading assessment:

“The Fountas & Pinnell BAS, a teacher-administered “running records” assessment, has been replaced by the computer-based and nationally normed iReady Reading Assessment.”

“Staff conduct continued universal dyslexia screening in grades K-three using the iReady assessment.”

District leadership:

“The district appointed our first-ever literacy director, a respected elementary principal with expertise in reading.”

“School administrators participate in monthly Elementary Principal Learning Collaborative meetings dedicated to pre-K-to-five reading instruction and supporting teachers with the implementation of curricular and assessment changes.”

School board:

“The school board has established multiyear improvement goals for third-grade student achievement, specifically focused on lower-performing student groups, to be included in the superintendent’s annual review.”

“District staff provides updates to the school board at least three times per year.”

Collins writes of the improvements:

“Over two years, we’ve seen significant improvement on the state’s CAASPP/Smarter Balanced assessments across all the targeted groups compared with 2019, despite the headwinds from the pandemic.”

“The bellwether low-income Latino third-graders have gone from 20% reading at or above grade level to 47% — one of the top results in the state.”

Collins continues:

“In fact, nearly all groups saw double-digit growth last year. The share of third-grade English learners reclassified to English proficient reached its highest level in at least the last 10 years. And last year’s third graders have held onto their gains in fourth grade.”

It’s not necessarily the case that increased investment leads to better reading scores. A 2023 report analysing charter schools in nine cities found that students perform better on reading tests and demonstrate greater cost effectiveness when it comes to reading and math. Example in the next section.

The highlight of the report is its claim that for every $1 invested in traditional public schools, students earn $3.94 in future lifetime earnings. That’s compared to $6.25 for charter school students. Unfortunately, the report did not investigate the reasons for this difference.

The authors found that when it comes to reading and math:

“Based on CREDO’s findings, we estimate that charter school students across nine cities perform 2.4 points (0.06 standard deviations, or SD) higher on the eighth grade reading NAEP exam and 1.3 points higher (0.03 SD) on the math exam, compared to matched TPS students.”

“We find that charter schools demonstrate an approximately 40 percent higher level of costeffectiveness than TPS on average across nine cities, earning an additional 4.4 points (0.12 SD or a 41 percent difference) on the eighth grade NAEP reading exam and an additional 4.7 points (0.12 SD or a 40 percent difference) in math per $1,000 of funding allocated per pupil (see Figure ES1).”

“Charter schools demonstrate a higher level of cost-effectiveness than TPS in seven cities; we find the largest gaps in NAEP points per $1,000 of funding in Indianapolis—an additional 11 points or 0.29 SD in reading (a 76 percent increase in cost-effectiveness) and an additional 12 points or 0.3 SD in math (78 percent increase). There are also large gaps in Camden, with an additional seven points or 0.18 SD in reading and eight points or 0.19 SD in math (103 percent increase for both), and San Antonio, with an additional four points or 0.11 SD in reading (25 percent) and five points or 0.12 SD in math (23 percent).”

Miami-Dade County Public Schools spends $9,240 per student per year, which is compared to more than $25,000 per student in New York and over $13,000 in Los Angeles and Chicago. This is because the district cuts back on staff numbers while still achieving better results than comparable large-city districts. Reports don’t explain what else they do, but the district teaches reading using phonics.

Miami-Dade County Public Schools achieves well-above average reading and math scores for a large-city district.

From 2009 to 2019, Miami’s fourth-grade reading scores grew by four scale points, although scores remained stagnant at eighth grade.

In 2019, it outperformed fourth-grade reading scores in large-city districts by 225 to 213 and in eighth grade by 262 to 255.

The NAEP found no district among TUDA participants that outperformed Miami in fourth or eighth-grade reading.

Miami-Dade Superintendent Alberto Carvalho attributes this to resisting the staffing surge seen in academic institutions since the 1950s, especially of administrative staff. Education Next reports that:

“Since 1950, the student population nationwide has doubled, or increased 100 percent, but the total number of school personnel has grown 381 percent.”

“The number of teachers grew 243 percent during that time and nonteaching staff grew 709 percent.”

From 1992 to 2015, “The student population grew by 19 percent, while the number of teachers rose 28 percent, and the number of all other staff grew 45 percent.”

But in Miami-Dade, “The number of students rose 16 percent, the number of teachers 35 percent, and the number (of) all other staff 18 percent.”

Carvalho took over in 2008 at the start of the financial crisis and quickly implemented a “zero-based, value-based budget” that went through all spending and analysed how each employee affected student learning.

Carvalho slashed the administrative staff roll by fifty-five percent, which allowed him to close one of the two central office buildings.

He says this was “not austerity, but cost reduction and realignment.”

Surveys conducted in 2016 and 2023 found that ninety percent of parents mistakenly believed their children were achieving on or above grade level in reading and math. Gallup notes this is a problem because parents are more likely to take action when they know their children are falling behind.

Gallup noted in 2023:

“Nine in 10 parents believe their child is at or above grade level in reading and math. If they’re using their child’s report card as a main indicator, it’s understandable, as roughly eight in 10 students in the U.S. receive mostly B’s or better.”

“However, when looking at other progress measures, including standardized test scores, a minority of students -- roughly less than half -- are performing at grade level.”

“When parents know their children are falling behind, they are more likely to prioritize reading and math and to take action.”

This figure hasn’t budged. In 2016, NPR reported:

“In a recent survey of public school parents, 90 percent stated that their children were performing on or above grade level in both math and reading. Parents held fast to this sunny belief no matter their own income, education level, race or ethnicity.”

A survey of 1,553 school districts found that even as more schools move towards the science of reading, many school system leaders are still instructing teachers to supplement their core offerings. Commentators warn that holding onto old methods and teaching with sections of different curricula can reduce the overall efficacy of teaching literacy.

The July 2025 survey used a nationally representative dataset and an “impact core” of large districts that together teach over half of America’s students.

The percentage of teaching with Heinemann’s Units of Study for Teaching Reading fell from nine percent in the 2023-24 school year to six percent in the 2024-25 school year.

The percentage of teaching with Fountas & Pinnell Classroom fell from 4.2 percent to 2.8 percent over the same period.

The most popular programs all have comprehensive phonics sections.

McGraw-Hill’s Wonders

HMH’s Into Reading

Amplify’s Core Knowledge Language Arts

Benchmark Education’s Benchmark Advance (*Some reports on forums say this one is less comprehensive)

But forty-eight percent of districts used at least two resources in ELA classrooms.

This can be fine if there’s a coherent strategy, but Brent Conway, the assistant superintendent of the Pentucket Regional school district in West Newbury, Mass, says he’s seen districts use a phonics program while continuing to use curricula that teach “three cueing.”

Kristen McQuillan visits schools and helps them transition from Balance Literacy towards research-backed practices. She says many schools struggle to leave behind old ways, something she calls “Balanced Literacy Rehab,” and identifies three warning signs that a school is struggling to transition:

Principals are unaware of whether the new program is being properly implemented.

Teachers are still using the old programs along with the new ones

The science of reading is implemented from kindergarten to second grade, but from third grade and up, teachers use old practices

Defenders of Lucy Calkins say her curriculum “opened conversations about power and justice” to students and blamed officials for not investing what was needed to make it work. The obvious rebuttal is that the goal of teaching young kids to read is not to expose them to conversations about power, and there’s no evidence that more investment would make Calkins’ curriculum work.

Dana Palubiak, a retired teacher from Missouri who taught grades two to four, says Calkins’ curriculum used “a workshop-style model that prioritizes student choice and independent learning.”

Palubiak praised Calkins for helping teachers open “conversations about power and justice to young learners,” such as through texts about segregation, the American Revolution, and Nazi Germany.

But even Palubiak acknowledged that Calkins’ curriculum by itself wasn’t enough; she had to supplement it with phonics.

However, Palubiak blames state and district officials who didn’t provide the investment and “scaffolding” needed to make Calkins’ curriculum work.

One interesting story Palubiak tells is of her time substituting at a school that taught phonics.

Palubiak complains that the children booed when she announced phonics time, not because of defiance, but because the children had already mastered reading.

And yet, Palubiak still had to devote the entire 40-minute block to teaching phonics.

But this is evidence that phonics work, and the problem is one of rigidity when it’s time to move on to independent reading.

Washington Post Article

Paul L. Thomas does not explain why over one-third of students reading at an NAEP level below basic is not a crisis. Firstly, it’s still a large number, and secondly, much research shows a link between lower reading ability and poor outcomes like school dropout rates, unemployment, and increased poverty.

Thomas states that:

“For over three decades, one-third of students have been below NAEP's ‘basic’ — a figure that is concerning but does not constitute a widespread reading crisis.”

But he never explains this assertion. One-third of students is a significant number, and failing to read at a basic level is a bad omen for their futures.

Researchers from the University of Virginia, the University of Memphis, and the American Institutes for Research in Washington, DC, conducted a study entitled ‘What Does “Below Basic” Mean on NAEP Reading?’ They found that,

“Compared with students who perform at the NAEP Basic level and above, students who perform below NAEP Basic are much more likely to have poor oral reading fluency and foundational skills.”

A 2015 UK study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies found a strong link between reading proficiency in schools at the age of ten and future earnings/wages. The authors stated, “We only present results controlling for both family background and the different skills individuals have,” and they find that reading skills are particularly important to students from poorer backgrounds.

A 2013 UK report found that “reading and maths abilities at age seven had a bigger effect on future socio-economic status than intelligence, educational level and social class in childhood.”

Admittedly, many studies cite socioeconomic status as an important determinant of future outcomes.

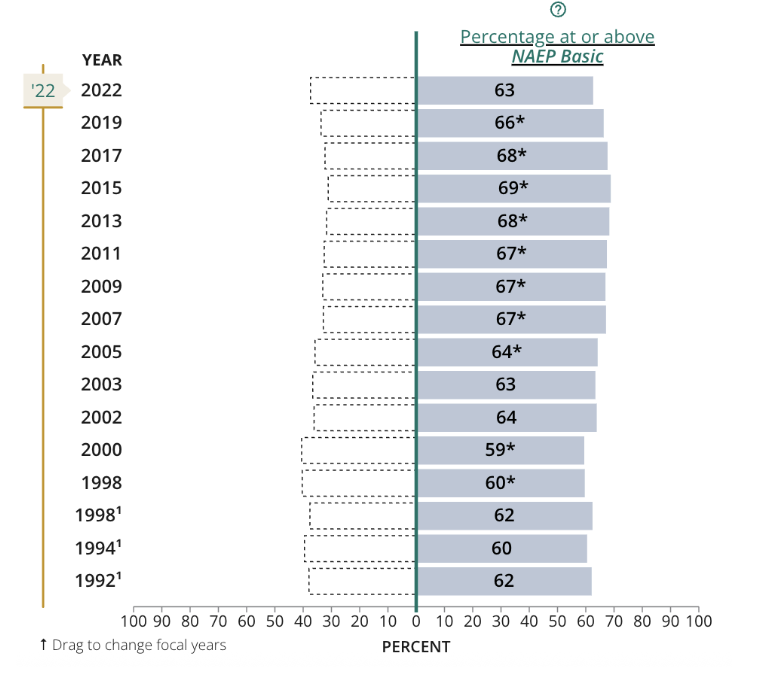

Thomas says the number of below-basic students in the NAEP has been consistently at one-third for more than three decades. That’s false, and the number has risen to forty percent since 2019.

Paul L. Thomas writes, “For over three decades, one-third of students have been below NAEP's “basic” — a figure that is concerning but does not constitute a widespread reading crisis.”

But the number was forty-one percent in 2000 and declined to around one-third, before rising again from 2019.

Thomas is selective with his phrasing because, since 2019, that number has been increasing, and now it’s at forty percent.

Thomas states that the real urgent matter in reading is to do with “addressing the opportunity gap that negatively impacts Black and Brown students.” But the latest NAEP reported increasing numbers of below-basic students from a large number of demographic backgrounds, and the real problem is a socioeconomic one.

According to the NAEP, “The percentages of fourth-grade students who performed at or above the NAEP Basic level in reading were lower for many student groups in comparison to 2019. For example, the percentages performing at or above NAEP Basic were lower in 2022 than in 2019 for the following student groups:”

Black and Hispanic students, students of Two or More Races, and White students;

Male and female students;

Students eligible and not eligible for the National School Lunch Program;

Students attending public schools;

Students attending public, non-charter schools;

Students attending schools in the Northeast, Midwest, South, and West regions;

Students attending schools in city, suburban, and town locations;

Students who were not identified as students with disabilities

Students who were not identified as English learners.

Natalie Wexler wrote in 2025 that she hopes for a change in the way gaps are reported:

“They’ve almost always been framed in terms of race and ethnicity rather than income or socioeconomic status (SES). That has been due partly to a lack of confidence in the standard measure of income.”

“Based on the new formula, 77 percent of students from high-SES families scored above the national average in reading, compared with only 32 percent of those from low-SES families. Of course, there are racial gaps too. For example, 64 percent of white students scored above average, versus 36 percent of Black students. But… I think SES rather than race goes to the heart of the reason that these test-score gaps exist and persist.”

Thomas’s main argument in The Washington Post is that the states measure reading proficiency at the NAEP basic level, and this is evidence that the NAEP test is too rigorous and thus overstating the crisis. Many researchers and commentators agree that it sets an impossible bar for the US.

Thomas’s argument boils down to the following points:

“The disconnect lies with the second benchmark, “proficient.””

“In almost every state, “grade level” proficiency on state testing correlates with the NAEP’s “basic” level; in 2022, 45 states set their standard for reading proficiency in the NAEP’s “basic” range. Therefore, it is inaccurate to say that nearly two-thirds of fourth-graders are not capable readers.”

“The NAEP has set unrealistic goals for student achievement, fueling alarm about a reading crisis in the United States that is overblown.”

Tom Loveless, an education researcher who previously worked for the Brookings Institution, tweeted that,

“The NAEP proficient standard was one of the worst policy decisions in history. It's so pie-in-the-sky that it later destroyed NCLB, which mandated 100% proficien(cy) in schools. Impossible, no country can do it, none can ever do it. Set back school improvement by decades.”

But Thomas fails to investigate the reverse implication, that local officials water down their thresholds to minimize the reading crisis in their states. This trend is known as the “honesty gap” and has received much criticism for masking slipping standards and misleading parents about performance.

In states with higher standards, there’s much political pressure to lower thresholds so as not to “unfairly mislabel” students. Illinois’s state schools chief, Tony Sanders, explained his potential decision to lower scores in the state by saying:

“Our system unfairly mislabels students as ‘not proficient’ when other data — such as success in advanced coursework and enrollment in college — tell a very different story.”

But this kind of thinking has led to what commentators call the “Honest Gap” about students’ academic performance. So much so, there’s even a dedicated website to the issue at honestygap.org.

Tom Kane, a Harvard researcher, criticized the lowering of proficiency standards following the pandemic for misleading parents about their children’s declining performance.

“Many parents are already underestimating the degree to which their children are lagging behind. Lowering the proficiency cuts now will mislead them further.”

In a 2023 email to staff, Jill Underly, Wisconsin's education chief, expressed confusion over the process of changing standards and questioned how parents were expected to follow.

Christy Hovanetz, a senior policy fellow at ExcelinEd, points out that these tests identify students who need help, and lowering standards might mean they slip through the cracks.

“These assessments are how we help identify students for extra support and assistance. Now there will be a lot of kids that aren’t going to be getting those high-dosage tutoring sessions or who aren’t going to be getting that additional support in math that they might need.”

Virginia has the lowest reading proficiency standards in America, but Gov. Glenn Youngkin is raising them from 2025-26 precisely so parents know the truth. States like Mississippi and Louisiana, which have improved proficiency, have also raised their cut-offs, suggesting that setting low standards is not conducive to raising performance.

Virginia is changing its rating system for K-12 schools from the 2025-26 academic year to highlight what Youngkin called a “catastrophic learning loss”.

Currently, around ninety percent of schools have received full accreditation for each of the last two years, but the change is expected to result in a majority of Virginia’s public schools being rated as “off track” or needing improvement.

Aimee Guidera, state education Secretary, said, “We are not telling parents, students, teachers, policymakers and citizens the truth about where our children really are on mastering content. Why isn’t there a sense of urgency?”

Critics say Youngkin is fueling a negative perception of schools to promote school choice. But Virginia suffered the steepest decline in fourth-grade reading on the 2022 NAEP test, falling from 224 to 214. In other measures, like the SAT, Virginia fares much better.

Virginia has the lowest standards in the country (source)

What’s more, Thomas ignores the fact that many people are aware that the NAEP test is more rigorous. But they’re less aware that states set seemingly arbitrary scores for reading proficiency, and these resulting differences in standards make state comparisons meaningless.

The New York Times reported on falling standards in January 2022, while noting Thomas’s concern:

“The NAEP exam is considered more challenging than many state-level standardized tests. Still, the poor scores indicate a lack of skills that are necessary for school and work.”

Lesley Muldoon, executive director of the National Assessment Governing Board, which sets policy for NAEP, points out that the national NAEP test:

“It is the only common yardstick that is available to compare student achievement across states and across the large urban districts… From the board’s perspective, standards are not going to be lower for [kids] when they enter college or the world of work.”

2022 State Mapping Analysis - 238 marks proficient on the 2022 NAEP test

Best Arguments for the Science of Reading

In response to falling literacy standards in the early 2000s, England introduced phonics instruction after a 2006 review and made such teaching mandatory from 2012. England immediately climbed up the international PIRLS rankings for reading. It should be noted that retention in English schools is practically unheard of.

England historically taught reading using a mixture of phonics and cueing, and literary scores were historically good.

But reading standards were slipping in England in the early 2000s, culminating in a sixteen-place drop in the international PIRLS rankings.

The government commissioned the 2006 Rose Review, also known as the “Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading.”

The report’s main recommendation was for “high quality, systematic phonic work,” or systematic synthetic phonics, to be the main way teachers instruct children in reading and writing.

Schools received guidance and training immediately, although mandatory phonics screening checks weren’t introduced until 2021, and this was for students at the end of Year 1.

Note: Reception is the first year of primary school (for children who are four at the start of the academic year), and Year 1 is the following year (for children who are now five).

What makes England a good poster child for phonics is that there’s a great comparison with the rest of the UK. Education is a devolved matter in the UK, so each of the four governments sets its own education policy.

England mandated phonics, as we have seen.

Northern Ireland doesn’t mandate phonics, but it’s still prominently used in schools. And because of failings in Scotland and Wales, Northern Ireland is now reviewing instruction to emphasize phonics.

Scotland and Wales do not mandate phonics and still use other instruction methods. Both countries regularly make bad headlines for reading, and Wales in particular is a notorious basket case when it comes to literacy.

Wales still regularly uses cueing to disastrous results.

One critic says proponents of phonics in England selectively choose 2006 as the starting comparison point because it’s most favourable, and the country has now simply returned to its high pre-phonics score. He (wrongly) claims that other countries have had comparable success without phonics, and supporters of phonics pick and choose their comparison countries.

Jeffrey Bowers, a professor of Psychological Science at the University of Bristol, wrote a lengthy 2022 blog post attacking supporters of the science of reading for their selective use of evidence. Among his criticisms are:

If you compare England’s reading results to those before the decline in results, around 2003, and before, then recent literacy results aren’t so impressive.

Northern Ireland, which is part of the UK, achieved even more impressive results without mandating phonics.

He criticises other researchers for comparing England’s results, a country that teaches with phonics, to Canada, a country that does not mandate phonics teaching.

England’s scores are inflated by the inclusion of private schools in the rankings. This matters because the phonics mandate didn’t apply to private schools.

However, the point is that standards had slipped and only returned to previous levels following the introduction of phonics. The comparable countries the researcher cites teach with phonics, and he is guilty of his own accusation, namely, ignoring countries that undermine his argument.

But there are obvious flaws in all his arguments:

Using 2006 as the comparison point is no less legitimate than using 2003; arguably, it’s more legitimate. Educators and officials had been warning of the decline in literacy standards for years, and the reversal in standards coincided with the adoption of phonics.

Northern Ireland doesn’t mandate phonics, but it’s still prominently used in schools. And because of failings in Scotland and Wales, Northern Ireland is now reviewing instruction to place an emphasis on phonics.

Bowers criticises researchers for choosing Canada, but he ignores by far the best comparisons to England, which are Scotland and Wales.

Neither country mandated phonics, Wales still regularly uses cueing to disastrous results. So they serve as excellent comparisons, given that both countries are part of the United Kingdom.

Both countries are basket cases when it comes to reading, at a time when England is being celebrated for its literacy success.

Note: Education is a devolved issue in the UK. That means each of the four countries of the UK is in charge of education in its own country. Wales and Scotland always elect very left-wing governments, so that explains their aversion to phonics.

Private schools will always inflate rankings because they take all the richest students (around 6-7% of primary school students). What’s more, many private schools also teach using phonics, but there’s no comprehensive data on this.

Mississippi’s defenders say improvements are not a result of gaming the system but a long-term concerted effort to raise standards. They add that Mississippi’s gains largely predate 2014/15, when the state began retaining students.

Rachel Canter is the executive director of Mississippi First, an education advocacy group based in the state.

In July 2023, she penned a scathing response to the LA Times article on Mississippi’s literacy gains.

Canter points out that Mississippi gained 20 scale points on the 4th-grade reading test between 1992 and 2019 (1992 was the first year that state NAEP data were released).

Most of these gains took place between 2005 and 2009, then between 2013 and 2019.

The LA Times article states that “Mississippi implemented what appeared to be an aggressive attack on its literacy shortcomings in 2013” through its Literacy-Based Promotion Act (LBPA). Canter retorts that:

Mississippi passed the LBPA in Spring 2013, and it didn’t go into effect for third graders until 2015. So the first students who experienced its effects were first tested in 2017.

But 15 points of Mississippi’s 20-point reading again had already happened by 2017. That means even if Mississippi was gaming the system with the LBPA, some 75% of the gains would still be unaccounted for.

The second point from the LA Times article is that “if you throw the lowest-ranking 10% out of a statistical pool, the remaining pool inevitably looks better.” Canter retorts that:

The 10% argument, if it were true, would only explain reading gains between 2015 and 2019. This period also constituted a minority of Mississippi's gains since 1992, nor were the gains unusual compared to the rest of the period.

The bloggers rounded up to 10%, something that statisticians avoid doing.

The retention rate caused by the LBPA has never been as high as 10%. The LBPA caused an initial increase of 5.75% to 5.91%, but after the first year, the retention rate started to fall back to pre-LBPA levels. By 2017/18, the retention rate caused by LBPA was no higher than 1.58% and the overall rate was less than 5%.

Canter makes more detailed points about this in the article if you’re interested. She also makes the point that these students don’t vanish and ultimately form part of the data.

Canter states that the real reason for Mississippi’s gains is “the effects of No Child Left Behind, the nationally aligned Mississippi College and Career Readiness Standards, and a comprehensive approach to improving education since 2012.”

The question is then how the science of reading can be responsible for gains made before its implementation in the 2014/15 academic year? Notably, there was a five-point jump between 2011-13; third-grade retention didn’t start until the end of 2014/5 but literacy measures were implemented from 2013/14.

Mississippi only started retaining third-graders in the 2014-15 school year, and so retention policies didn’t affect NAEP-tested groups until later.

The biggest gains were from 2013 to 2015 when there were no retentions. ExcelinEd also says that retention is falling in Mississippi because:

“More teachers and coaches trained in the science of reading, and consequently, it became easier to identify students who needed additional intervention.”

Reports claim that Mississippi has been more rigorous in implementing the science of reading measures, whereas other states, like Oklahoma, have diluted their measures.

ExcelinEd claims that Mississippi succeeded where others failed because the state was more rigorous in implementing the science of reading.

“The early literacy efforts in Mississippi included a state-funded commitment to a pre-kindergarten pilot program; a comprehensive reading policy featuring a promotion/retention component at third grade; and a required assessment of the knowledge and skills needed to teach the science of reading for aspiring elementary teachers.

“Additionally, the state adopted new, rigorous standards in 2010, which were being phased in by grade with the expectation of statewide implementation during the 2015-2016 school year. While state legislation was a first step, implementing the standards simultaneously statewide required an unprecedented coordination of efforts among many groups.”

“Mississippi spent two years rolling out the new law and standards; hiring and training reading coaches; ensuring new curricula were in place; and answering lots and lots of questions from educators, families and school leaders.”

OCPA, citing sources from ExcelinEd, notes that Mississippi and Oklahoma introduced literacy at similar times. Initially, Oklahoma received similar acclaim for its improvements on NAEP, but in 2014, state lawmakers gutted its reading laws under House Bill 2625.

Oklahoma’s scores have been declining ever since, despite increasing per-pupil spending by 47% from 2013 to 2014.

The number of third-graders that Mississippi retains fell between the 2018-19 and 2022-23 school years, from 9% of students to 6.5%.

From Mississippi Today in May 2024

Country Overview

The three NAEP oral fluency studies all found a correlation between comprehension as measured by the regular NAEP test and oral reading fluency. However, the studies don’t offer specific data for states, nor can the 2018 study be compared to previous studies because of changes in methodology.

The 2018 study was “administered to a nationally representative sample of 1,800 students between January and March of 2018 (and) it measured students’ oral reading fluency in terms of speed, accuracy, and expression.”

The more regular NAEP reading test assesses passage comprehension only.

However, the 2018 report found a strong relationship between NAEP reading comprehension scores and oral reading fluency, as well as pseudoword and word reading.

The 2002 study likewise found a strong correlation between comprehension and oral fluency.

According to the 1992 study, “oral reading fluency demonstrated a significant relationship with reading comprehension”.

The study was previously carried out in 2002 and 1992, but the NAEP warns that the studies aren’t comparable because of changes in the design of the study.

The 2018 study was administered on tablets to small groups of students simultaneously in one room, all of whom wore headsets with noise-canceling microphones while seated in a cardboard carrel. The previous studies were administered one-to-one.

The 2018 study was graded using natural language processing scoring algorithms.

The 2018 study followed a “cold read” procedure that’s now common in oral reading fluency tests. The previous studies allowed students a silent read before they read aloud.

Even Science of Reading advocates note that the NAEP isn’t a measure of the best instructional methods.

Natalie Wexler, author of “Beyond the Science of Reading,” told EdSurge that the NAEP is only a rough measure of a student’s reading ability rather than an indication of the best instructional methods.

Wexler added that the NAEP doesn’t claim to measure a student’s ability to decode words but is instead about comprehension.

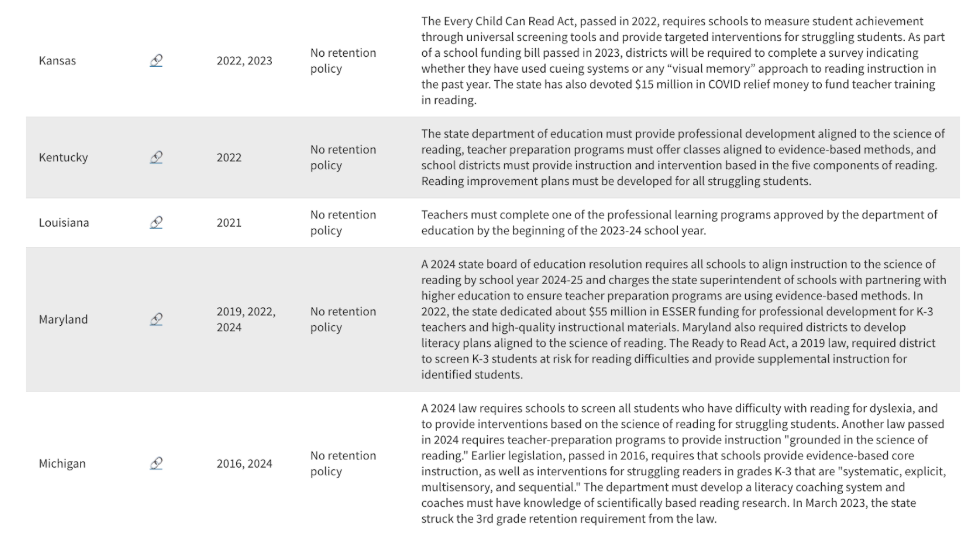

Forty states plus the District of Columbia have passed “science of reading” laws, while twenty-six states plus the District of Columbia allow or require schools to retain third-graders who aren’t reading at a proficient level.

The Education Commission of the States reported in January 2024 that:

“13 states plus the District of Columbia require retention for third-grade students who are not reading proficiently, and 13 states allow retention decisions at the local level.”

“Arkansas, Louisiana and West Virginia are implementing retention laws in the coming years.”

“Michigan repealed its law, effective March 2024. Finally, a bill passed one chamber in the Ohio Legislature that would eliminate third-grade retention requirements.”

Note: There are sixty-two laws below for the forty states plus D.C.

Details about each state’s reading laws

Note: In the link column below, you’ll see a little icon. If you enter this Education Week's site, then those icons are links to the relevant state laws.

Florida’s Reading Scores

Florida’s reading scores peaked around 2009 and stayed at that level until 2017, when they began to decline. The state then experienced a decline of seven points from 2022 to 2024, equivalent to the nineteen years of gains from 2002 to 2022. Republicans blame the administration of the NAEP test, while left-wingers blame underinvestment and policy

Florida’s historical gains are attributed to phonics reforms, but it’s unclear why the state suffered a steeper drop relative to the national dip.

Most observers point to pandemic disruptions or other national trends, but these aren’t specific to Florida.

It should be noted that mid-year monitoring of fourth and eighth-grade reading, released in January 2025, showed an improvement in state assessments.

Some Florida-specific explanations include:

Local media reports that some schools in Florida have been particularly badly hit by hurricanes over the last few years.

The Florida Education Association said the results were the “long-term consequences of underinvestment, overburdened educators, and bad policies…”

Education Commissioner Manny Diaz criticized the “major flaws in (the) methodology” of the test under Biden’s Department of Education.

Diaz also said that the test “fails to account for Florida’s educational landscape,” such as the 524,000 students on a school choice scholarship in private or home schools that aren’t included in the NAEP results (which is for public school students only).

Diaz again criticized the test for disproportionately selecting urban and underperforming schools. But Florida signed off on the selected schools.

While the “Mississippi Miracle” has given the state much attention, it’s Florida’s 2002 law that makes it the original southern trailblazer when it comes to reading scores. That’s why many of the southern states' literacy policies mimic Florida’s.

Florida mainly used whole language instruction in the 1980s and 1990s, but then Governor Jeb Bush signed the “Just Read, Florida!” initiative in September 2001, which began a push for phonics instruction in the state.

Florida, like a lot of the U.S., taught reading using the “whole language” instruction method, which had been prevalent since the early 1980s.

Governor Bush signed Executive Order 01-260 on September 7, 2001, which led to the subsequent launch of the “Just Read, Florida!” initiative.

Florida modeled the program after the Reading First initiative, which prioritized explicit, systematic phonics in literacy. This federal initiative used the framework detailed by a 2000 National Reading Panel report.

Florida mandated third-grade retention from the 2002-03 school year for students underperforming on the former state standardized test, the FCAT. Exemptions and provisions foreshadowed those of other southern states, likely because Bush advocated them through his advocacy group ExcelinEd.

The Florida legislature mandated that pupils who scored under Level 2 (out of five performance levels) on the Florida Comprehensive Assessment (FCAT) must be retained in the third grade.

Districts had to inform parents if their child was deficient in literacy and tell them about the retention policy.

Districts then had to provide annual reports of progress to the parents of retained students.

Districts also had to give intensive remediation measures to retained students. According to the Helios Education Foundation, this included:

“Summer reading camps”

“Academic improvement plans”

“Ninety minutes of daily research-based reading instruction”

“Assignment to a ‘high-performing teacher’ in the retention year”

The exemptions to the policy were, according to the Helios Education Foundation:

Students with limited English proficiency

Students with a severe disability

Students who scored above the 51st percentile nationally on another standardized reading test,

Students who had been retained twice previously

Students who demonstrated proficiency through a portfolio of work.

Jeb Bush promoted Florida’s literacy laws through the advocacy group he founded, ExcelinEd in Action. The group encourages states to base their education policies on Florida, where Bush was governor. ExcelinEd played an important role in supporting Mississippi’s 2013 law.

Some 27,713 students were retained in Florida from the 2002-03 school year, equating to 14.4 percent of all students. In 2001-02, just 3.3 percent of students were retained. The number of retained students quickly fell as a result of more exemptions and better performance on the FCAT.

The number of retained third-graders jumped from 6,435 in 2001-02 to 27,713 in 2002-03, equating to a jump from 3.3 percent to 14.4 percent.

But the number of good cause exemptions jumped from just over 13,000 in the first two years of the policy to more than 20,000 by the third year of the policy.

The number of third-graders achieving a Level 1 and thus qualifying for retention decreased from twenty-three percent in 2002-03 to a low of fourteen percent in 2005-06.

However, it’s not clear that retention drove improved literacy scores in Florida as the state implemented many measures from the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s. What’s more, the above chart on FCAT scores shows third-grade reading scores also improved, which occurred before retention could take place.

The above chart shows that the number of third-graders achieving a Level 1 and thus qualifying for retention decreased from twenty-three percent in 2002-03 to a low of fourteen percent in 2005-06.

But retention doesn’t occur until the end of the third grade. So if third-graders’ scores are improving, this means

The Helios Education Foundation notes that correlation doesn’t imply causation, especially when Florida implemented numerous literacy measures, making it challenging to isolate retention as the primary driver of improvement. The included:

Governor Jeb Bush’s A+ Plan (1999 to 2007)

Just, Read, Florida! (2001)

An effort to reduce class sizes (2002)

Federal Reading First (2002)

Establishment of the Florida Center for Reading Research (2002)

Several other policies, including school choice and charter schools

Mississippi’s Reading Scores

Summary: Retention is not inflating Mississippi’s literacy rates, but extra resources for failing students are likely helping. Phonics has helped Mississippi, but much of the state’s success predates the effects of its implementation. Mississippi spent decades implementing training programs to raise literacy standards, and its success can be attributed to this general long-term effort. The real southern trailblazer is Florida under Jeb Bush, which inspired its southern neighbours to tackle literacy.

Interactive graphs in the link

Florida’s 2002 law made it the original southern trailblazer when it comes to reading scores, which is why the state’s neighbours followed its lead (graph link)

The most common explanation for Mississippi’s literacy gains is the 2013 passage of the Literacy-Based Promotion Act. Studies have shown that states that implemented similar policies also made bigger reading gains (but many of their gains predate the effects of this law, more than two sections below).

A 2023 study found that Mississippi students retained in third grade went on to make big gains in their test scores.

“Retention led to large improvements in ELA scores, though we find no significant impacts in math. The test score impacts are driven by Black and Hispanic students. Retention did not significantly impact attendance rate or the likelihood that a student is later classified as having a disability.”

A June 2023 study by the College of Education at Michigan State University revealed that states that implemented a series of sixteen policies supported by ExcelinEd made bigger reading gains than states that implemented some or no policies.

ExcelinEd is an advocacy group founded by Jeb Bush. The group encourages states to base their education policies on Florida, where Bush was governor. ExcelinEd played an important role in supporting Mississippi’s 2013 law.

However, LA Times columnist Michael Hiltzik controversially accused Mississippi of gaming its scores. His first accusation is that the state retains failing third-graders to inflate its gains, and his second accusation is that gains “vanished by the eighth grade”. Chalkbeat dismissed these points and stated that the gains are “legitimate and meaningful,” with little proof that results are inflated.

Hiltzik used the work of bloggers Bob Somerby and Kevin Drum as the foundation of his argument.

Hillztik said that any literacy gains made in fourth-grade scores had disappeared by eighth grade, claiming that students achieved the same results in 2022 as in 2013.

Hillztik and his bloggers also claimed that if you added the nearly 10% of held-back third-graders (the most of any state) back into the pool, the gains from 2013 completely vanished.

Drum concluded, “In other words, the 2013 reforms had all but no effect.”

But Chalkbeat assessed Hiltzik's article and found it lacking. Hiltzik’s claim that holding back third-graders inflates scores doesn’t make sense.

You might improve test scores for the first year by taking the worst performers out of the pool, but these students aren’t held back forever, so long-term data won’t be affected.

Chalkbeat also assessed Hiltzik’s claim that literacy gains had disappeared by eighth grade as “misleading” to say the least.

Mississippi roughly halved its test score gap with the rest of the US in eighth grade. That’s not as big as its fourth-grade gains, but it’s significant.

What’s more, eighth-grade scores may continue to increase because fourth-graders who took the NAEP in 2019 hadn’t reached eighth grade to take the 2022 exam by the time of the results.

Andrew Ho is a testing expert at Harvard University and a former member of the board that oversees NAEP. Like Hiltzik and the bloggers, he says his instinct is to challenge big test score gains. But he said of Mississippi,

“I don’t see any smoking guns or red flags that make me say that they’re gaming NAEP.”

The number of third-graders that Mississippi retains fell between the 2018-19 and 2022-23 school years, from 9% of students to 6.5%.

From Mississippi Today in May 2024

An executive director of Mississippi First says that No Child Left Behind and a long-term concerted effort to raise standards achieved the gains. The executive also criticized many aspects of the LA Times article; it’s ignorant of the fact that Mississippi’s gains date back to 2005, which undermines many of the article’s points, and it overstates the number of third-graders being held back (which is, in any case, irrelevant).

Rachel Canter is the executive director of Mississippi First, an education advocacy group based in the state.

In July 2023, she penned a scathing response to the LA Times article on Mississippi’s literacy gains.

Canter points out that Mississippi gained 20 scale points on the 4th-grade reading test between 1992 and 2019.

Most of these gains took place between 2005 and 2009, then between 2013 and 2019.

1992 was the first year that state NAEP data were released.

The LA Times article states that “Mississippi implemented what appeared to be an aggressive attack on its literacy shortcomings in 2013” through its Literacy-Based Promotion Act (LBPA). Canter retorts that:

Mississippi passed the LBPA in Spring 2013, and it didn’t go into effect for third graders until 2015. So the first students who experienced its effects were first tested in 2017.

But 15 points of Mississippi’s 20-point reading again had already happened by 2017. That means even if Mississippi was gaming the system with the LBPA, some 75% of the gains would still be unaccounted for.

The second point from the LA Times article is that “if you throw the lowest-ranking 10% out of a statistical pool, the remaining pool inevitably looks better.” Canter retorts that:

The 10% argument, if it were true, would only explain reading gains between 2015 and 2019. This period also constituted a minority of Mississippi's gains since 1992, nor were the gains unusual compared to the rest of the period.

The bloggers rounded up to 10%, something that statisticians avoid doing.

The retention rate caused by the LBPA has never been as high as 10%. The LBPA caused an initial increase of 5.75% to 5.91%, but after the first year, the retention rate started to fall back to pre-LBPA levels. By 2017/18, the retention rate caused by LBPA was no higher than 1.58% and the overall rate was less than 5%.

Canter makes more detailed points about this in the article if you’re interested. She also makes the point that these students don’t vanish and ultimately form part of the data.

Canter states that the real reason for Mississippi’s gains is “the effects of No Child Left Behind, the nationally aligned Mississippi College and Career Readiness Standards, and a comprehensive approach to improving education since 2012.”

The Washington Post editorial board cited several studies that linked retention to improved literacy but questioned whether it’s retention that’s improving literacy rates or the package of programs given to retained students. The Post attributed the success to the Mississippi’s training of literacy coaches.

The Post notes that over a dozen states mandate retention, while others permit it at parents’ and schools’ discretion. The policy appears to improve literacy rates in schools.

A FutureEd report studying literacy policies during the 2010s found that states that used retention policies achieved greater progress in test scores.

A Boston University study about Mississippi found that “for students who were in the third grade in 2014-15, being retained under Mississippi’s policy led to substantially higher ELA scores in the sixth grade.”

The effect was much more significant than other educational interventions and was driven by Black and Latino students.

But the Post stated that “it is impossible to disentangle retention itself from all that comes with it.”

Retained students are offered after-school tutoring, summer programs, or specialized instruction during school hours.

But retention is also unpopular with students, and schools would prefer not to do it because of the cost.

The Post attributes Mississippi’s success to the “painstaking” job of training and monitoring teachers and students with the science of reading.

“In Mississippi, literacy coaches have been painstakingly selected, trained, and monitored by the state and dispatched to perform one job: supporting teachers as they learn and learn to teach, the science of reading. Teacher preparation programs have evolved to encompass these methods. The curricular materials recommended by the state match up, too. When kids fall behind, they’re identified and they’re given aid.”

Hechingher Report also dismissed the LA Times' criticisms and called the gains genuine. The publication also praised Mississippi’s training programs on phonics, which in some cases predated the 2013 passage of the Literacy-Based Promotion Act (LBPA).

The Barksdale Reading Institute has provided private funding to help push the science of reading in Mississippi, which is now a big component of the Literacy-Based Promotion Act.

Hechingher Report says this is only possible because of teachers and the resources made available to support reading instruction.

The LBPA provides state funding for assistant teachers from kindergarten through third grade. The act also provides additional training and access to literacy coaches.

One example is Reading Universe, which offers online class videos, teacher interviews, and comprehensive guides to support literacy teaching, including identifying phonemes.

One explanation for why gains predated the LBPA is that literacy faculty at teacher preparation institutions spent years discussing how to prepare teachers to teach literacy in early grades.

Some commentators say the improvement is not to do with teaching or curriculum, but because Mississippi revamped its state test to align it more with NAEP. Commentators say this could explain some inflation in scores as students are trained to take a specific exam rather than becoming better educated, but again, this falls into the same trap as criticisms that ignore the pre-2017 improvement.

By training students to take a specific exam, students may achieve better scores on that test without becoming better educated. Andrew Ho, a testing expert at Harvard University and a former member of the board that oversees NAE, says,

“To the extent you prioritize NAEP, you risk inflating NAEP scores”.However, Chalkbeat points out that this isn’t a bad thing if the test is a good reflection of what students should learn.

Furthermore, Mississippi first started recording improvements in 2013, while the change in testing started in 2015.

Another argument is that Mississippi hasn’t improved its literacy; rather, the rest of the country has regressed. But the obvious counter to the point is to ask why Mississippi didn’t also regress?

Douglas Carswell, President & CEO of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy and former British MP, says that the state’s education rankings are down to a decline in national standards.

Carswell points out that while Mississippi rose from 46th to 18th for fourth-grade reading between 2015 and 2022, the average fourth-grade NAEP reading score only rose from 214 to 217.

He adds that there has been no progress in the past five years and that all improvements are certainly the result of the 2013 literacy laws, which emphasized phonics.

Carswell’s two points are easily dismissed.

The state is obviously doing something right to improve literacy at a time when national standards are falling.

Carswell acknowledges in his article that the improvements came before 2019, but is unaware that the first cohort of students to be affected by the 2013 literacy laws was not assessed until 2017.

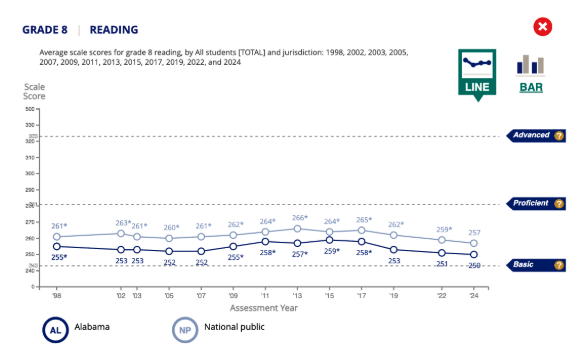

Alabama’s Reading Scores

Summary: The state’s success in reading is attributed to the 2019 Alabama Literacy Act. While there are fears that thousands of students are being retained, the truth is that fewer than 1% of third-graders fail to advance to fourth grade, and Alabama’s results are stagnant rather than improving

The 2019 Alabama Literacy Act requires schools to retain third-graders who fail to meet reading benchmarks. The law came into effect for the 2023-24 school year.

Alabama’s 4th-grade reading scores have fallen since a 2011 peak and remain stagnant.

Alabama’s 8th-grade reading scores follow the national trend. But the interesting data will come in the next few years when the kids taught under the recent changes reach 8th grade.

Alabama third-graders have a number of opportunities to progress to fourth grade. First, they sit a spring test measuring reading “sufficiency,” which a large majority of students pass. Then they can attend summer reading camps, retest, demonstrate progress with a portfolio of work, or apply for good cause exemptions. But reading “sufficiency” doesn’t mean students are “proficient.”

Alabama administers a spring reading test to all third graders to check that they are reading “sufficiently” before they can be allowed to advance to fourth grade. Alabama Daily News notes the following about definitions regarding reading tests:

“‘Sufficiency’ is a measure lower than grade-level and distinct from ‘proficiency’... The terms are not interchangeable and have caused confusion among educators and parents alike.”

While 91% of third-graders were “sufficient” in reading in 2024, just 63% were proficient “on the full English language arts section of the ACAP.”

If the spring test finds that a third-grade student is reading sufficiently, then they automatically advance to fourth grade without further tests.

Students who fail to read sufficiently have several options, including:

Non-mandatory summer reading camps involving sixty hours of reading instruction.

Retesting or demonstrating progress with a portfolio of work.

Good cause exemptions.

Alabama is increasing its cut score, which in turn affects the percentage of students who are deemed “sufficient” readers. Changes to testing mean you can only compare third-grade reading scores from the 2022-23 school year.

The recommended reading score for third-grade students to be at grade level is 473.

2020-21 & 2021-22: Alabama did the same test, but based on the old standards. The cut score was two standard errors of measurement below, but the raw number was different as a result.

In school years 2022-23 & 2023-24, the cut grade was 435. That’s two standard errors of measurement below 473.

In the school year 2024-25, the cut grade was 444. That’s 1.5 standard errors of measurement below 473.

In the school year 2026-27, Alabama intends to raise the cut grade to 454.

Some 91% of third-grade students achieved the benchmark score of 435 on their spring reading test in 2024. That compares to 83% in 2023.

However, Alabama Daily News points out that this means 91% of third-graders were “sufficient” in reading. Just 63% were proficient “ on the full English language arts section of the ACAP.”

Reports claimed that as many as 24% of the state’s third-graders were being retained, with the state superintendent estimating it would be 10-12,000 students. However, data from the 2023-24 school year revealed the true figure is 452, or less than 1%, and the real concern is that students are advancing despite achieving insufficient reading scores.

Alabama Daily News said that previous testing suggested up to 24% of students could be retained. Eric Mackey, Alabama’s State Superintendent, estimated at the start of the 2023-24 school year that between 10-12,000 third-graders would be retained.

However, once the final report arrived in January 2025, Alabama Daily News revealed that,

“Alabama schools held back 452 third graders at the end of the 2023-24 school year because of the accountability requirements of the Alabama Literacy Act. That figure represents less than 1% of the 55,100 third graders statewide, according to data from the Alabama Department of Education.”

The spring reading test highlighted some 4,800 third-graders who could not read at a “sufficient” level to advance automatically to fourth grade.

Over 3,000 third-graders retested over the summer, and almost half achieved the benchmark score to advance.

The Associated Press then ran a report headlined “An estimated 1,800 students will repeat third grade under new reading law.” But this fails to take into account exemptions.

Alabama Daily News says it’s unclear what’s happened to the roughly 1,700-1,850 students who continued to read insufficiently. But 2,052 third graders whose reading skills continued to be deemed insufficient advanced to fourth grade under good cause exemptions:

1,553 of these students had disabilities and “received two years of intervention or had been previously retained.”

396 students were “English learners with less than three years of English instruction.”

103 students “received intervention for more than two years and were retained for two years in previous grades.”

Alabama Daily News adds that:

“While half of K-3 students were eligible for the camps, 22% attended.”

Shelley Vail-Smith, President of the Alabama Campaign for Grade-Level Reading, says that promoting failing readers without the right interventions leads to an inevitable cycle of failure.

“We know that more than 452 third-grade students statewide didn’t have the skills they needed to be successful in fourth grade. The issue becomes what we did with those students who lacked the skills and were promoted anyway. Did we close the gap from where they were at the end of third grade until now?”

Louisiana’s Reading Scores

Louisiana’s fourth-grade students have led the U.S. in reading growth for two consecutive NAEP cycles, albeit during a time of national decline. But unlike Alabama, their eighth graders are also making improvements. A press release from the Louisiana Department of Education singles out the science of reading as the reason for this improvement.

The Louisiana Department of Education said in a January 2025 press release announcing the latest results that:

“Louisiana’s academic progress reflects the state’s emphasis on foundational skills and its investment in educators. Literacy instruction aligned to the Science of Reading: Louisiana implemented a comprehensive literacy plan rooted in phonics, transforming how reading is taught statewide and equipping educators with the training to help students thrive.”

Louisiana jumped from 50th in 4th-grade reading in 2019 to 16th in 2024 by increasing its score from 210 to 216.

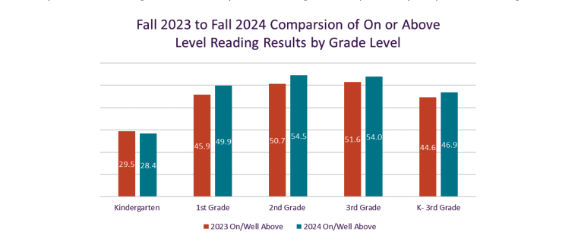

State testing shows noticeable improvement from 1st grade through to 3rd grade, but a dip for Kindergarten students. However, 2023’s kindergarten class grew by 20.4% in 2024 as first graders. Prior state reports don’t offer helpful comparisons to measure improvement.

A press release by the state education department notes that:

“The overall proficiency rate improved for grades K-3 by 2.3 percentage points to 46.9 when comparing 2023 to 2024.”

“First grade grew by 4 to 49.9, second grade by 3.8 to a 54.5, and third grade by 2.4 to a 54.”