Assisted Dying Programs Across The Globe

A review of the literature

by John Morrison

November 15, 2024

Global Overview of Laws

Map of jurisdictions where AD/AS is currently legal in some form (from the UK Parliament)

Comparison of medically assisted dying legislation (from Forbes)

Country/State Comparison of Assisted Dying Deaths

The Netherlands leads the ray with assisted dying rates, followed by Canada, Belgium, and Switzerland

Rates per 1,000 deaths excluding external causes (from N-IUSSP)

Canada is a global outlier in how quickly assisted dying rates are increasing.

Table 1 presents five-year rates of EAS deaths per 1,000 deaths not due to external causes from the first full year of introduction of the measure, also displayed in the table.

Some countries and US states, such as Switzerland, Luxembourg, Spain, California, Washington, and Oregon, had a relatively slow start.

In others, such as Belgium and Colorado, levels have been systematically higher from the outset, as is the case in the Netherlands, where assisted suicide had been decriminalized long before the 2001 law that made it legal, and Canada, definitely an outlier in this respect.

Rates of change (from N-IUSSP)

The speed of growth in the various countries also varies. Table 2 shows the average annual rate of increase in EAS for each five-year period of existence of the law.

Growth was generally rapid at the beginning then slowed down later on.

However, in many countries, it picked up again between the third and fourth five-year periods.

The average annual growth rates are below 10% per year in the Netherlands and Oregon, between 10% and 20% in Switzerland, Oregon, and Washington, and above 20% per year in Belgium, Luxembourg, and two US states (Colorado, and California). Canada also stands out in this respect, with an EAS growth rate of almost 50% per year.

Rates of change (from N-IUSSP)

In Canada, a record 15,280 euthanasia deaths were recorded in 2023, up from 1,018 in 2016.

An incomplete breakdown of Canada’s ten provinces in 2023 is as follows:

Saskatchewan, for example, saw an increase of more than 25 percent year over year, from 257 MAiD deaths in 2022 to 344 in 2023.

Nova Scotia had 342 euthanasia deaths in 2023, also an increase of 25 percent.

B.C. which had one of the highest rates of euthanasia in 2022, reported 2767 MAiD deaths in 2023, a 10 per cent increase compared to the previous year.

Quebec, which has the highest percentage of MAiD deaths – 7.3 percent of Quebec deaths were by euthanasia, the highest percentage in the world – had a 17 percent increase in such deaths to a total of 5686.

Ontario had 4461 euthanasia deaths (up 18 percent )

Alberta reported 977 euthanasia deaths (18 per cent increase).

Manitoba had 236 euthanasia deaths in 2023, a six percent increase from the 223 the province had in 2022.

Total euthanasia deaths in Canada (from The Interim)

In the Netherlands, there were 9,068 notifications of euthanasia in 2023.

Assisted deaths in The Netherlands

In Belgium, the country reached a record high of 3423 assisted dying deaths in 2023. In addition to these euthanasias officially declared to the Commission, scientific studies estimate that approximately 25 to 35% of undeclared euthanasias should be added.

Euthanasia deaths in Belgium (from the IEB)

In California, some 884 individuals died with assisted dying in 2023, down slightly on 2022’s record high of 890 individuals.

Pg 4 of CDHP report

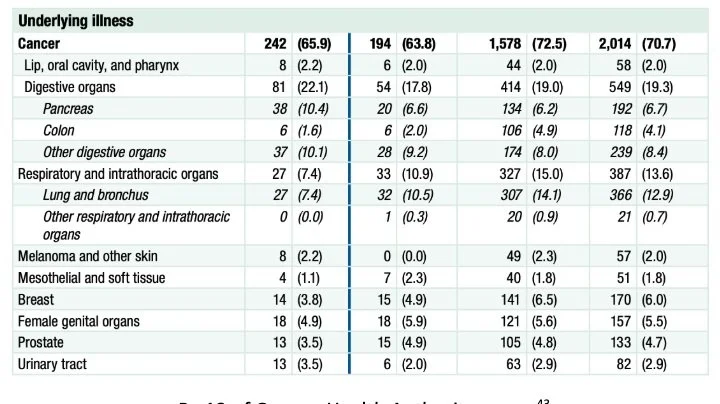

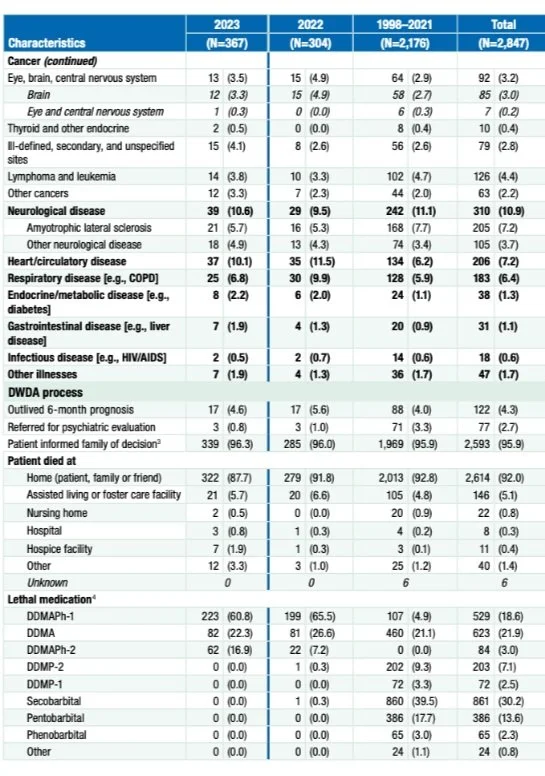

In Oregon, some 367 individuals are reported to have died with help from the program, while 560 people received prescriptions.

During 2023, 560 people received prescriptions for lethal doses of medications under the provisions of the Oregon DWDA, compared to 433 reported in 2022 (Figure 1).

As of January 26, 2024, OHA had received reports of 367 people who died during 2023 from ingesting the medications prescribed under the DWDA, an increase from 304 in 2022.

Since the law was passed in 1997, a total of 4,274 people have received prescriptions under the DWDA and 2,847 people (67%) have died from ingesting the medications. During 2023, DWDA deaths accounted for an estimated 0.8% of total deaths in Oregon.*

Pg 16 of Oregon Health Authority report

More Detailed Statistics from the Netherlands

The split between male and female patients was almost 50-50.

As in previous years, the number of notifications concerning men and women was almost the same: 4,603 men (50.8%) and 4,465 women (49.2%).

A majority of the 9,068 deaths suffered from cancer. Meanwhile, neurological disorders, a combination of conditions, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disorders made up a large share.

Page 14 of RTE Report

In 2023, 138 euthanasia notifications concerned patients whose suffering was (largely) caused by one or more psychiatric disorders.

Page 16 of RTE Report

Some 7,151 deaths occurred at home with the rest a mix of hospitals, nursing homes, and hospices.

Pg 19 of RTE report

A 29-year-old Dutch woman was granted her request for assisted dying on the grounds of unbearable mental suffering.

Zoraya ter Beek received the final approval last week for assisted dying after a three-and-a-half-year process under a law passed in the Netherlands in 2002.

Her case has caused controversy as assisted dying for people with psychiatric illnesses in the Netherlands remains unusual, although the numbers are increasing.

In 2010, there were two cases involving psychiatric suffering; in 2023, there were 138: 1.5% of the 9,068 euthanasia deaths.

More Detailed Statistics from Belgium

Around 79% of patients in 2023 were expected to die in the short term. Patients who did not meet this criteria suffered from multiple pathologies.

In the vast majority of cases (79.2%), the physician considered that the patient's death was foreseeable in the short term.

Patients whose death was clearly not expected in the short term mainly suffered from multiple pathologies, whereas the death of cancer patients is rarely considered as such.

Most Belgian cases in 2023 involved cancer or a combination of several chronic refractory conditions. Some 1.4% involved psychiatric conditions.

The breakdown is as follows:

The conditions causing euthanasia were tumors (cancers) (55.5%)

A combination of several chronic refractory conditions (poly pathologies) (23.2%)

Diseases of the nervous system such as ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease (9.6%)

Diseases of the circulatory system such as a stroke (3.2%)

Diseases of the respiratory system such as pulmonary fibrosis (3%)

Psychiatric conditions such as personality disorders (1.4%)

Cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer's disease (1.2%)

Diseases of the osteoarticular system such as arthropathies or myopathies (0.7%)

Traumatic injuries such as a complication following surgery (0.6%).

The other categories all together represent 1.2% of the conditions.

Half of euthanasias were performed in a home setting in 2023, while 17.6% took place in nursing homes and a further 32% in hospitals or palliative care units.

The percentage of euthanasias performed at home decreased further in 2023 (48.6% compared to 50.5% in 2022)

While the percentage of euthanasias performed in nursing homes and rest and care homes continued to increase (17.6% compared to 16.4% in 2022)

The percentage of euthanasia performed in hospitals and palliative care units remained stable (32% compared to 31.8% in 2022).

110 patients traveled from abroad to access the programme and 101 of these individuals resided in France. But only 60% of these patients were expected to die in the short-term.

According to Part II of the declarations, in 2023, 110 patients residing abroad came to Belgium in order to benefit from euthanasia under the conditions of Belgian law.

Since the indication of the place of residence is not mandatory in this part, this is the minimum number.

This concerns patients suffering from neurological conditions, tumors, or multiple pathologies.

Some 60 % of deaths were expected in the short term. Patients were mainly aged 50 to 89 years.

These patients resided mainly in France (101). Other countries of origin mentioned were: Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, England, Italy, and South Korea.

More Detailed Statistics from California

Some 884 individuals died from euthanasia in 2023, down slightly from 2022’s record high of 890 individuals, most of whom suffered from cancer.

According to the California Department of Public Health, for the calendar year ending December 31, 2023:

1,281 individuals received prescriptions under the EOLA; and

884 individuals died following their ingestion of the prescribed aid-in-dying drug(s), which includes 49 individuals who received prescriptions prior to 2023.

Of the 884 individuals:

92.8 percent were 60 years of age or older;

97.1 percent had health insurance; and

93.8 percent were receiving hospice and/or palliative care.

Since the law came into effect June 9, 2016, through December 31, 2023:

6,516 individuals have been written prescriptions under the EOLA;

4,287 individuals, or 65.8 percent, have died from ingesting the medications; and,

Of the 4,287 individuals, 3,911, or 91.2 percent, were receiving hospice and/or palliative care.

Pg 4 of CDPH Report

Pg 8 of CDHP Report

Pg 14 of CDHP report

Pg 15 of CDHP Report

Over 92% of Californians who died with assisted dying were aged 60 or over and the split was even between men and women, while white people made up over 85% of patients.

Pg 11 of CDHP report

Page 13 of CDHP Report

Interestingly, over half of people who died with assisted dying held a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, or a doctorate, while another 18.7% had some college education.

Pg 12 of CDHP Report

More Detailed Statistics from Oregon

Most individuals were white and received a high level of education.

Pg 11 Oregon Health Authority Report

Most individuals suffered from cancer while the rest suffered mainly from neurological diseases, heart disease, or respiratory disease.

Pg 12 of Oregon Health Authority Report

Pg 13 of Oregon Health Authority Report

California vs. Canada

California and Canada’s programs share many commonalities: similar population size, both began in 2016, similar healthcare, and similar North American culture.

Trying to understand such differences between countries is usually very difficult because so many other factors are also different. But, as it happens, California and Canada are easy to compare:

Both started allowing MAiD in 2016

Both have large diverse populations of a similar size (39 and 35 million respectively)

Both have populations who mostly speak English

Both share the same North American popular culture

Both have government-provided Medicare for everyone 65 and older, the people who are most likely to use MAiD; the big difference between the US and Canada is that everyone in Canada gets Medicare, not just older people like in the US

Both have a healthcare system staffed primarily by independent physicians free to choose their own patients and free to provide only those medical services they feel are personally acceptable; in other words, no physician in California or Canada is forced to offer MAiD

Adrian Byram, an EOLCCA Board director, and his colleague Peter Reiner, a professor in the Psychiatry Department at the University of British Columbia, conducted a study. It found no difference in people’s belief about moral acceptability or willingness to use MAiD themselves, and Canada had more palliative care options.

The 2024 study is called “Disparities in Public Awareness, Practitioner Availability, and Institutional Support Contribute to Differential Rates of MAiD Utilization: A Natural Experiment Comparing California and Canada”.

It found no difference in:

People’s belief about moral acceptability: slightly more Californians (70%) believe MAiD is morally acceptable than Canadians (65%), no matter whether MAiD has to be self-administered like in California or can be physician-administered like in Canada

People’s willingness to use MAiD themselves: just about 50% of both Californians and Canadians say they would definitely or probably choose MAiD if they were suffering from a long and painful disease like cancer. Again, whether MAiD would be self- or physician-administered made no difference to people’s willingness to use it.

Availability of palliative and hospice care: The inability to get palliative care doesn’t seem to mean you are more likely to choose MAiD. In 2023 more Canadians (58%) had palliative or hospice care at the time of their death than did Californians (42%)

Why people choose MAiD: about 65% of the people choosing MAiD in both Canada and California have cancer; most of the others had similarly intractable diseases like ALS or COPD.

But Canadians are choosing MAiD 16 times more often to escape the very same diseases that cause grievous suffering for Californians. A key difference that could explain the discrepancy is how widely the two programs are promoted.

Californians don’t know that MAiD is one of their legal rights, and California’s healthcare institutions do not make it easy to access MAiD.

Only 25% of Californians know MAiD is even available let alone that it is their legal right.

While 67% of Canadians know MAID is their legal right.

All Canadian healthcare institutions let everyone know that MAiD is available.

They list MAID along with all the other services they offer and make professionally staffed MAID Care Coordination teams available to everyone.

In California, healthcare institutions similarly use their websites to describe their many treatment and wellness services, but mention MAiD (if at all) on pages accessible only by diligent searching.

Only one big healthcare institution – Kaiser Permanente – is an exception, and even so, it’s not immediately obvious how to find out about MAiD on their website.

One caveat to the study is that it claims Canada has more restrictive guardrails in place but we know these are deeply flawed.

The study makes the following point on the restrictiveness of the respective laws: except for allowing medical practitioners to provide MAiD by injection, the Canadian law is more restrictive, with tougher eligibility guardrails and a requirement for the medical practitioner to obtain the patient’s consent one last time immediately before administering MAiD.

The New Atlantis Essay - Canada’s Euthanasia Program

Euthanasia is when a medical practitioner directly administers a lethal injection whereas assisted suicide is when patients are given the means to end their life. Canada’s MAID encompasses both but over 99% of deaths are euthanasia.

Canada calls it Medical Assistance in Dying, or MAID.

The term encompasses both assisted suicide, which is when providers give patients the means to end their own lives, and euthanasia, which is when a medical practitioner directly administers a patient’s lethal injection. But virtually all such deaths — over 99.9 percent — are euthanasia.

Supporters insist that this is not state-sanctioned suicide. Rather, it’s a dignified solution for those who no longer wish to suffer from terminal or chronic illness.

MAID allows “for compassionate action, while also protecting those who are particularly vulnerable,” claimed David Lametti, the attorney general and minister of justice, in 2021.

At the heart of Canada’s medical system is a strange balancing act - there’s a national suicide prevention hotline but also euthanasia hotlines. The idea is that the country protects vulnerable people who want to die for the wrong reasons while helping legitimate cases.

Doctors and nurse practitioners are now in the business of saving the lives of some patients while providing death to others.

There is a national suicide prevention hotline you can call 24/7, where sympathetic operators will try to talk you out of killing yourself.

But today there are also euthanasia hotlines, where operators will give you the resources you need to carry out your wish.

This is the promise of medical assistance in dying: that vulnerable people who want to die for the wrong reasons will be encouraged to live, as they always have been — while people who want to die for the right reasons will have their autonomous decision upheld.

If even a single vulnerable person were pushed into assisted death, it would be a scandal to the system. That is why safeguards were put into place.

But an increasing number of anecdotal reports suggest this is failing, including an incident where a veteran asking for a wheelchair was asked if she’d like to apply for euthanasia.

And yet stories describing just this — a system that does encourage the vulnerable to seek medical death — are coming fast and hard lately.

A number of recent news articles have reported on Canadians who, driven by poverty and a lack of access to adequate health care, housing, and social services, have turned to the country’s euthanasia system.

In multiple cases, veterans requesting help from Veterans Affairs Canada — at least one asked for PTSD treatment, another for a ramp for her wheelchair — were asked by caseworkers if they would like to apply for euthanasia.

Everyone from Justin Trudeau to the Supreme Court to the CBC and euthanasia advocates have made clear that the safeguards will and do work.

Justin Trudeau made a clear promise to the public: that nobody would receive MAID “because you’re not getting the support and care that you actually need.”

In its ruling decriminalizing the practice asserted that the MAID system was to be “carefully-designed” with “stringent limits” to prevent abuse. That was the charge put to the government by the Supreme Court of Canada in its 2015 ruling decriminalizing the practice.

The court affirmed that “a permissive regime with properly designed and administered safeguards” would be “capable of protecting vulnerable people from abuse and error.”

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 2017 assured its readers that it is a “misconception” that “MAID puts vulnerable people at risk.”

James Cowan, a former senator who helped lead the passage of the original legislation, said in 2021:

“We have four or five years of experience now, and absolutely no indications, that I’m aware of, of alleged misuse or poor decisions.”

Helen Long, the CEO of Dying with Dignity Canada, offered this line in a May 2022 Maclean’s essay, arguing that the stories that people:

“Who are not able to access supports like safe and affordable housing are opting to have MAID instead” are “simply not true and there is no evidence that I’m aware of to support those claims.”

The New Atlantis Essay - CAMAP’s Coverup

However, CAMAP, a leading Canadian euthanasia provider, has sat on credible evidence from its own members that people are being driven to euthanasia by credit card debt, poor housing, and difficulties getting medical care.

In July 2022, Health Canada, the agency that is responsible for national health care policies, announced a plan to outsource its voluntary euthanasia training standards to CAMAP.

Stefanie Green is president and co-founder of the organization, also known as CAMAP. It is not a government entity, but Green also stresses that it “is not an advocacy movement.”

Instead, she says, it exists to fill “an absolute void” of interpreting federal law to clinicians.

The organization’s website says it aims “to establish training resources, to create medical standards, and to encourage the standardization of care across the country.”

CAMAP holds regular training sessions and The New Atlantis obtained video recordings of many from 2020 through to 2022. In one, a retired care coordinator lists multiple examples of patients with non-fatal conditions who sought euthanasia as a result of their poverty and lack of available support.

The organization regularly holds virtual seminars aimed at training euthanasia assessors and providers.

The New Atlantis has obtained video recordings of several seminars held from 2020 through 2022, along with slideshows and material used by the presenters.

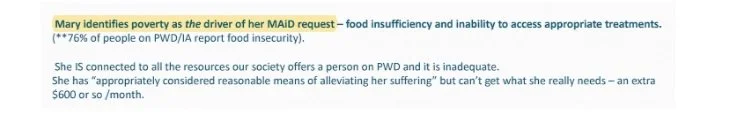

Althea Gibb-Carsley recently retired as a care coordinator and social worker of Vancouver Coastal Health’s assisted dying program. The title of her presentation asks, “What is the role of the MAID assessor when resources are inadequate?” She describes several cases that she managed as a care coordinator.

Take Mary, 55, who Gibb-Carsley says is “bright, creative, tenacious, determined” — “a dynamite person.”

Mary has worsening fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue, both non-terminal medical conditions. (Gibb-Carsley doesn’t specify whether she is using real names or not.)

Mary knows that she could control her pain if she could take vitamin pills, eat a special diet, and goes to physiotherapy.

She can’t afford it. “Mary identifies poverty as the driver of her MAID request,” Gibb-Carsley writes on a slide accompanying her talk, emphasizing that “She does not want to die, but she’s suffering terribly and she’s been maxing out her credit cards. She has no other options.

A slide from Althea Gibb-Carsley’s CAMAP presentation (from the New Atlantis)

Then there is Nancy, 68, a former physician, and Greg, 57, a writer:

Nancy is “bright, capable, she’s tired, very, very tired.” But following a car accident, Nancy now has chronic pain. “She believed she had a lot more years to work,” so she didn’t save enough money.

Greg is a writer who has diabetes, cardiac problems, anxiety and depression, and a history of trauma.

Both need housing, but they can’t find any place that is accessible, safe, and affordable on an income mostly from disability benefits.

The end is predictable. “Nancy has no other options,” while Greg’s “plan was to stretch his credit to the edges and then set a final date.”

A slide from Althea Gibb-Carsley’s CAMAP presentation (The New Atlantis)

Lucy, a 38-year-old trans woman, is an immigrant who has pain, osteoarthritis, depression, and anxiety.

Although Lucy is “clever” and her college program is funded, it’s hard for her to concentrate on her studies, and “people are so judgey.”

She lives in a new one-room studio that has “no air or light and creepy men all around.”

Lucy was waiting for the law to expand to allow euthanasia not only for terminal illness but for any “grievous and irremediable” condition.

It is a vague standard, and some reporting suggests it could include osteoarthritis, the only diagnosed physical condition Lucy is described as having.

We do not hear what happened to Lucy, but the expanded eligibility standard she was waiting on did take effect in 2021.

Then there is the problem of doctor shopping. If a doctor dutifully screens for eligibility and rejects someone, then the person can just go elsewhere. Ellen Wiebe approved a man previously rejected for MAID and picked him up at the airport before bringing him to her clinic to euthanize him.

In a CAMAP seminar recording, we learn of a man who was rejected for MAID because, as assessors found, he did not have a serious illness or the “capacity to make informed decisions about his own personal health.”

One assessor concluded, “It is very clear that he does not qualify.”

But Dying with Dignity Canada connected him with Ellen Wiebe (pronounced “weeb”), a prominent euthanasia provider and advocate in Vancouver.

She assessed him virtually, found him eligible, and found a second assessor to agree.

“And he flew all by himself to Vancouver,” she said. “I picked him up at the airport, um, brought him to my clinic and provided for him,” meaning she euthanized him.

Even doctors can doctor-shop. There is one final procedural safeguard: a second assessment by a clinician that agrees with the first. In practice, it’s nearly impossible not to meet this requirement and the system makes it easy to die.

Jocelyn Downie, a prominent law professor who was part of the legal team that won the court case decriminalizing euthanasia, tells assessors and providers during a seminar that,

“You can ask as many clinicians as you want or need.” Seemingly implying that you can do so until there is a concurring opinion.”

Disagreement doesn’t mean you must stop,” she says in another seminar.

MAID assessments are highly subjective. We hear as much from the presenters in the CAMAP training seminars.

Some physicians believe that advanced age should help qualify a person. Others don’t.

In one session, a presenter says that providers “have a lot of different ideas” about how to assess whether someone suffering from Alzheimer’s has the capacity to choose euthanasia.

It’s as if there are as many views of rational suicide as there are assessors.

“There is no certainty or unanimity required. There is no perfection required,” says Downie.

The result: There are many paths available to reach the end, and you only need to find one. The system makes it easy to die.

The New Atlantis Essay - Lack of Safeguards

A core reason that Canada’s assisted dying program has grown so much faster than any other program in the world is that it is the most permissive.

Eligibility criteria began loose and are rapidly getting looser. You do not need to be terminally ill, only to have a “grievous and irremediable” condition, a standard that is open to significant differences in interpretation.

In March 2023, mental illness alone will qualify as an acceptable medical reason to die.

The Quebec College of Physicians now suggests that Parliament expand euthanasia eligibility to minors and even newborns.

Canadians were promised a system that would distinguish a rational choice to die from a desperate cry for help. But depressed people can be rational in explaining decisions they don’t want to be making.

This is particularly true in cases where a patient seeking euthanasia has a history of depression. As the psychiatrist Paul Appelbaum told The New Atlantis:

“People with depression can be extremely rational in explaining the reasons for the decisions that they’re making. And what is most difficult is to separate the effect of the depression on that decision from what their underlying non-depressed motivations might be.”

According to an internal study of MAID assessments, presented to CAMAP in 2022, of 54 patients who were not terminally ill, two-thirds had concurrent mental illness.

A fifth of the patients had difficulty finding “appropriate” treatment.

Most disturbingly, over a third of patients were “not offered appropriate/available treatments.”

Canadian law requires that a qualifying medical condition for MAID be “incurable” and “irremediable.” But providers already have ample evidence that their patients’ conditions might be remedied if they could access better resources and medical care.

In testimony to a parliamentary committee, Wiebe said that she would consider a patient on a five-year waitlist for an effective treatment to have “irremediable suffering.”

Recognizing the need for guidance, CAMAP developed generalized assessment forms and many doctors now use these to evaluate whether a person is eligible for MAID. One expert said the forms cannot identify patients who should be given help while another called it “death by checklist.”

The New Atlantis sent them to Paul S. Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University in New York City. Appelbaum, a leader in his field, has been practicing for four decades.

In 1998, he helped develop a now widely used test for assessing whether patients are mentally competent to make medical decisions.

In 2022 an expert panel convened by the Canadian government recommended his competency test to euthanasia assessors, an indication that Appelbaum’s authority is recognized by the MAID system itself.

“All in all,” says Appelbaum by email, “it doesn’t strike me as a particularly well-thought-through evaluation process.”

Among other things, “it’s not clear from these forms how an evaluator would decide that a condition is ‘grievous and irremediable,’” he says, quoting one of the key legal criteria.

Moreover, the initial screening questions for depression and anxiety:

“are not detailed enough to result in a diagnosis, and even if they did, the impact the answers to these questions are supposed to have on the final decision about authorizing MAID is unspoken.”

This matters because another key criterion is that patients be mentally competent to request their own deaths.

What Appelbaum is saying here is that a person who may be depressed and suicidal — who ought to be helped to find hope, not encouraged to die — cannot properly be identified with these forms.

The New Atlantis also sent the CAMAP forms to Mark Komrad, a clinical psychiatrist and ethicist who helped craft the American Psychiatric Association’s statement against euthanasia for patients who are not terminally ill.

His response was a single line: “Death by checklist!”

Part of what Komrad means is that the checklists are a tool available to MAID assessors, rather than a safeguard imposed upon them — they are not set by federal law.

So in practice, the law leaves a great deal of latitude to euthanasia providers to decide whether the requirements are met.

Much as the man with a hammer comes to see everything as a nail, again and again, Canada’s euthanasia system looks at vulnerable people and sees good candidates for medical death. Patients now increasingly turn to MAID where in the past they would’ve pursued treatment.

Catherine Frazee, a disability scholar, told The New Atlantis by email about a doctor colleague who:

“Has observed patients who become fixated on MAID, who under different circumstances, before MAID was a part of our culture, would have carried on living through difficult times, or who would have pursued treatment options with a reasonable chance of success even though doing so would be temporarily unpleasant or uncomfortable. Many people who are not at risk of suicide are nevertheless at risk of MAID, especially because it has been so quickly embraced as an honorable, “dignified,” idyllic form of death.”

You even hear this firsthand from some euthanasia providers — like Madeline Li, who told Parliament:

“I’ve certainly had cases where I felt compelled to provide MAID against my better clinical judgment because the law did not adequately protect.”

You hear it too from psychiatrists like John Maher, editor of the Journal of Ethics in Mental Health, who told Parliament that he has patients who could get better but,

“Are now refusing effective treatment to make themselves eligible for MAID.”

Ellen Wiebe

Ellen Wiebe is a board member and the research director of the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers (CAMAP). Wiebe splits her time between euthanasia and abortions.

Dr. Ellen Wiebe is a Clinical Professor in the Department of Family Practice at the University of British Columbia.

After 30 years of full-service family practice, she now restricts her practice to women’s health and assisted death.

She is the Co-Director of Willow Clinic in Vancouver and she is a board member and the research director of the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers (CAMAP).

Wiebe is one of Canada’s most prominent practitioners of Maid, having helped some 430 people die in the country in 2016. But Trudo Lemmens, a professor in health law and policy at the University of Toronto says Wiebe doesn't have the clinical expertise to assess someone’s suffering.

However, it is the profile of her patients that has generated controversy:

A high-flying businesswoman diagnosed with dementia in her fifties

A military veteran suffering from PTSD and chronic pain. “He could have lived for decades more,” Wiebe admits.

Then there is the case of a 56-year-old woman with advanced multiple sclerosis who, in 2017, starved herself to ensure her death was “reasonably foreseeable” — a key criterion that must be met for securing Maid.

Wiebe duly fulfilled her wish to die.

Trudo Lemmens, a professor in health law and policy at the University of Toronto, describes Wiebe and other providers’ work as “deeply disturbing”.

He does not believe that Wiebe, a former GP, has the clinical expertise to assess and determine someone’s suffering, “which is complex, which has to be addressed by societal support, by specialized care, by improvements in the healthcare system”.

For Wiebe, there is no debate: every patient should have the right to self-determination. “People are facing death and they want some control, and I’m in a position to help them have that control over their dying process,” she says.

Wiebe, however, is clear that she would help end the lives of the mentally unwell.

“There’s no question that people with mental illness suffer terribly,” she says. “I would be okay with it if it was legal but it’s not.”

Ellen Wiebe approved a man previously rejected for MAID and picked him up at the airport before bringing him to her clinic to euthanize him.

In a CAMAP seminar recording, we learn of a man who was rejected for MAID because, as assessors found, he did not have a serious illness or the “capacity to make informed decisions about his own personal health.”

One assessor concluded, “It is very clear that he does not qualify.”

But Dying with Dignity Canada connected him with Ellen Wiebe (pronounced “weeb”), a prominent euthanasia provider and advocate in Vancouver.

She assessed him virtually, found him eligible, and found a second assessor to agree.

“And he flew all by himself to Vancouver,” she said. “I picked him up at the airport, um, brought him to my clinic and provided for him,” meaning she euthanized him.

Ellen Wiebe described her euthanasia efforts as “the most rewarding work we’ve ever done” and said that people who are lonely or poor have the right to die. She laughed about angry family members being their greatest risk and has described deaths as “beautiful.”

And even if the safeguards were more rigorous, they wouldn’t do much good, because the enforcement has been lax.

Criminal investigations of MAID providers are exceedingly rare, and CTV News reported in 2022 that “federal officials don’t keep statistics on when such cases are reported to police.”

Nancy Hansen, the Director of the Disability Studies program at the University of Manitoba, told me that in effect “there’s no consequences for non-compliance” with the law.

And that’s because the people doing the training, the assessments, the procedure, and informing the review are all the same people.

These are the people, as Ellen Wiebe says often in her public speaking, for whom this is “the most rewarding work we’ve ever done.”

Wiebe described a recent procedure she performed, saying, “It was a beautiful death.”

And she admitted that the real difficulty is not protecting the vulnerable from abuse: “Angry family members are our greatest risk,” she says, and laughs.

Wiebe declined the request to be interviewed for the New Atlantis article. Asked for comment about her statements in the seminar, she responded:

“It is rare for assessors to have patients who have unmet needs, but it does happen. Usually, these unmet needs are around loneliness and poverty. As all Canadians have rights to an assisted death, people who are lonely or poor also have those rights.”

An Orthodox Jewish nursing home accused Wiebe of "sneaking in and killing someone" but she was cleared of wrongdoing by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C.

The Louis Brier Home and Hospital filed a complaint last year after Dr. Ellen Wiebe provided a resident with medical assistance in dying (MAiD) on site in 2017.

Barry Hyman, 83, had lung cancer and was suffering the after-effects of a stroke, and had insisted on a medically assisted death in his room at the nursing home.

His family made a formal request for him to do so, but it was denied.

In an interview with the Vancouver Sun last year, Louis Brier CEO David Keselman described Wiebe's actions as "borderline unethical."

"We have a lot of Holocaust survivors. To have a doctor sneak in and kill someone without telling anyone, they're going to feel like they're at risk," Keselman was quoted as saying.

Keselman said the nursing staff had to deal with the “traumatic” news from a Hyman family member that the man they had seen 10 minutes before was dead.

“That was tough on our staff,” said Keselman. “This isn’t an acute-care facility.”

Wiebe, on the other hand, believes religious facilities like Louis Brier should not be able to implement blanket bans on medically assisted deaths.

"It's so very important that we understand that it's not an institution or a building that has conscience rights. It is only people who do," she said.

In a July 5 letter, the college's lawyer informed Wiebe she would not face any discipline for helping Hyman defy the rules and die in his room.

In November 2024, a judge blocked Wiebe from euthanizing a woman with bipolar disorder in a last-minute decision following an application for an injunction by the woman’s partner. In the claim, the woman’s partner argued that the woman’s condition does not make her eligible for euthanasia.

The injunction, granted by British Columbia judge Justice Simon R. Coval, prevents doctors from approving euthanasia or assisted suicide for the unnamed 53-year-old woman from Alberta for Canada for 30 days.

The decision came the day before the woman was supposed to be euthanized.

In the claim, the woman’s partner argued that the woman’s condition does not make her eligible for euthanasia. It states,

“Her condition is one of mental illness or disability, rather than a physical malady, and because it is not an ‘irremediable’ medical condition”.

The woman, who has bipolar disorder, was unable to find a doctor who would approve her for euthanasia until she discovered Vancouver doctor Ellen Wiebe who boasts about having ended the lives of over 400 of her patients via euthanasia.

The woman had admitted herself to the hospital after an “intense manic phase”, after which she underwent treatment that led to “negative side effects”.

After conducting her own research, she concluded she had “akathisia“, a condition that the Court characterizes as “restlessness, terror, agitation, inability to sit still and burning skin sensations”. The Court heard that akathisia is treatable but Dr Wiebe approved her for euthanasia regardless.

While a judge prevented euthanasia from being administered in this particular case, it is a temporary injunction, and in September this year, the euthanasia lobby group, Dying with Dignity Canada lodged a court appeal, arguing that it is discriminatory towards people with mental illness that those suffering physically can access euthanasia and assisted suicide but those with mental illnesses cannot.

In their case, Dying with Dignity is accusing the Government of breaching section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom, which states that each Canadian citizen has the “right to life, liberty and security”.

It also accuses the government of breaching section 15, that citizens should not be discriminated against based on “mental or physical disability“.

Its press release argues that the exclusion of people with mental illnesses from assisted suicide and euthanasia “reinforces the stigma and historic prejudice against people with mental illness”.

Stefanie Green

Stefanie Green is a co-founder and the current President of the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers (CAMAP), she is a co-lead for the Canadian MAiD Curriculum Project. In addition to euthanasia, she is also trained in infant male circumcision.

She is a medical advisor to the BC Ministry of Health MAiD oversight committee, a moderator of CAMAP’s national online forum, has provided expert testimony to the Canadian House of Commons and the Senate, and has hosted several national conferences on the topic of assisted dying.

She is a member of the clinical faculty at both the University of British Columbia and the University of Victoria and has published an internationally bestselling memoir – This Is Assisted Dying – A Doctor’s Story of Empowering Patients at the End of Life – about her first year of providing this care.

Initially trained in infant male circumcision during her family medicine residency in Montreal, Dr. Green began providing circumcisions in Victoria BC in 2012.

Stefanie Green angrily denied that people are accessing MAID because of financial and housing problems. But when The New Atlantis confronted her with evidence this was happening she refused to comment.

Asked on a call with The New Atlantis about stories of abuse, Green raised her voice and said, “You cannot access MAID in this country because you can’t get housing. That is clickbait. These stories have not been reported fully.”

But Green was asked more than two days before this article went to press how she reconciles the seminar recordings with her earlier claim that stories of abuse are “click bait” that “have not been reported fully.”

Green requested and was provided information on how to access the recordings discussed in this article, but she did not offer a comment.

The New Atlantis asked Stefanie Green how she would judge the competence of a patient with a mental health condition. Paul S. Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University in New York City, said her distinction doesn’t make any sense.

When The New Atlantis asked Stefanie Green how she decides whether a patient with a mental health condition has the competence to choose euthanasia, she said that she makes a judgment call about whether a patient has an “active” or “stable” case of mental illness.

For “active” cases, she will consult a specialist; for “stable” cases, she proceeds on her own.

Green is not a psychiatrist, so The New Atlantis asked Appelbaum about her framework.

“It’s not a distinction that makes any sense to me,” he says.

This is a problem not only for Green. Under federal law, any physician or nurse practitioner can assess a patient and provide euthanasia, and in many provinces, they can do so without any additional required training.